Diseñado para celebrar y fortalecer la identidad cultural, 'Colombia Colores' ofrece una experiencia alegre e inmersiva donde los niños exploran la herencia colombiana a través del canto, la narración de3 May 2023

Read MoreHealing Young Minds Affected by Trauma

How does Children Change Colombia work to reduce the trauma and stigma faced by survivors of child recruitment in Colombia?

Adriana* was a rural girl that loved to live in the countryside with her family but at a young age she was forced to join the guerrilla in Colombia. That was a very sad and difficult period in her life and the things she had to see and was forced to do are unimaginable.

After the peace agreement between the government and the guerilla, Adriana joined the government program for children who have been victims of child recruitment. She was placed in one of CRAN’s foster homes in Bogotá a year ago when she was 14 years old. At the time, she was emotionally vulnerable and had difficulties coping with her day-to-day life. She had experienced bullying at school and had difficulties with social communication and interaction.

Since joining the project, Adriana has made significant progress with her personal and psychosocial skills, for example when expressing her needs and emotions. These skills have been developed through participating in training, cultural and recreational activities at the project.

She says, “My experience in art therapy activities has strengthened and helped me much more in my personal relationships and my capacity to express what I feel and to be myself”. She was also able to talk about plans for her future, showing interest in studying a technical or professional career.

Trauma and Stigma affecting Survivors of Child Recruitment

Violence and poverty in Colombia have led to thousands of children being recruited into armed groups, while many others remain involved in other criminal activities. As a result, the mental health of these young people has become a pressing issue.

The latest analysis of mental health in Colombia (2020), based on the data from the Ministry of Health (Sistema de Información de Prestaciones de Salud – RIPS), shows a high demand for services related to mental and behavioural healthcare, with an increase over the years. Exposure to violence has resulted in adverse effects on the mental health of children, particularly for those who have escaped armed groups and now have to deal with their trauma, as well as the stigma and isolation that comes with reintegrating back into society.

According to the National Center for Historical Memory (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica), the dimension of children and young people recruitment is such that, from 1958 to 2020, more than 17,860 minors have been victims of forced recruitment by armed groups. Regarding children at risk of joining criminal activities, according to the Colombian Social Services in the last 5 years over 15,000 children and young people (between the ages of 14 and 17) have gone through restoration of rights facilities in Colombia.

The vast majority of these children and young people have been disproportionately affected by violence, poverty and exclusion which has left them more likely to be exposed to health disparities with already limited access to mental and physical health services. They come from the most marginalised neighbourhoods and regions in Colombia where children often suffer neglect, intra-familial violence, and lack a support network within their family or community. These risk factors and the exposure to such dangerous and violent events has resulted in several adverse effects on the physical and mental health outcomes of these CYP, particularly relating to trauma and their reintegration into civilian life where stigma and discrimination have worsened their mental health and wellbeing. It is claimed that “youth who are both victimised, and delinquent have more adversities, lower levels of social support and higher rates of mental health symptoms”.

Psychologically, children in this situation lose their childhood, and lose their possibilities of recreation, study, and family time. Additionally, their reintegration process is marked by fear, mistrust, anguish, dread, difficulty in assuming new challenges, loss of autonomy and other challenges that affect their behaviour and mental health. This is due to their uncertainty towards an unknown environment, as they have never been fully integrated into their communities. Many of these young people also have severe substance abuse problems and emotional instability which began before entering the institutional programmes.

Furthermore, from our experience, the children that are part of these institutional programmes for reintegration and rehabilitation can experience new traumas resulting from the social exclusion they face. They often feel displaced, uprooted and isolated which can cause emotional crises, anxiety and depression. Most Colombians have been scarred one way or another by the conflict and violence; having been recruited or involved in criminal activities as minors, children formerly associated with armed groups, involved in criminal activities or are at risk to do so, are also victims of this violence, but many people, including their families, either do not understand or do not accept this which creates hostile environments and stigma towards them.

CCC joined efforts with the local grassroots organisations Fundación Cran and Tiempo de Juego in Bogotá and Villavicencio to support these children. Continue reading to learn more about our new mental health and elimination of stigma project.

Children Change Colombia’s new mental health project

Our partner CRAN works in Restrepo (Meta) where children face a high risk of recruitment by armed groups. They also provide foster homes and psychosocial support to children formerly associated with illegal armed groups in Bogotá and Villavicencio. These children were forcibly recruited by the guerrilla and it is very dangerous for them to go back to their hometowns so they are in these cities to be in a safe home and recover from the trauma they have experienced, as well as helping them to develop the life skills necessary to reintegrate into society, to access state support, and to navigate the legal system if necessary.

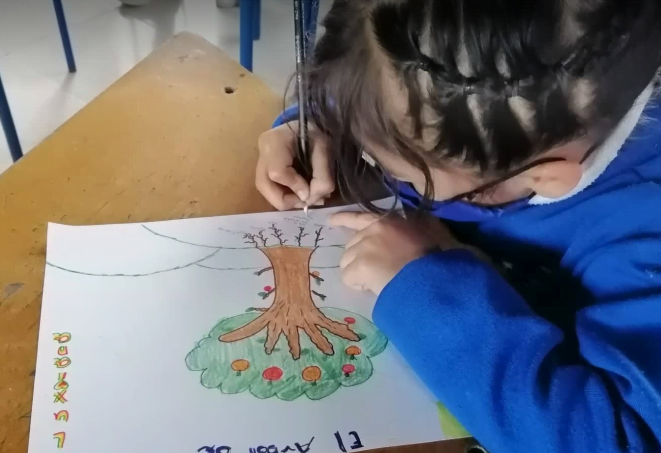

The children of the project took part in an art therapy activity where they created pieces of art in response to the question ‘what does peace mean for you?’ The activity brought up memories from their childhoods and hometowns when they were happy and peaceful. The participants came from all over Colombia and their artwork was reflective of their culture and regions. The artworks were successful in allowing the teenagers to create positive narratives for themselves. They were displayed in different public buildings around Bogotá, so people could better understand their dreams and lives.

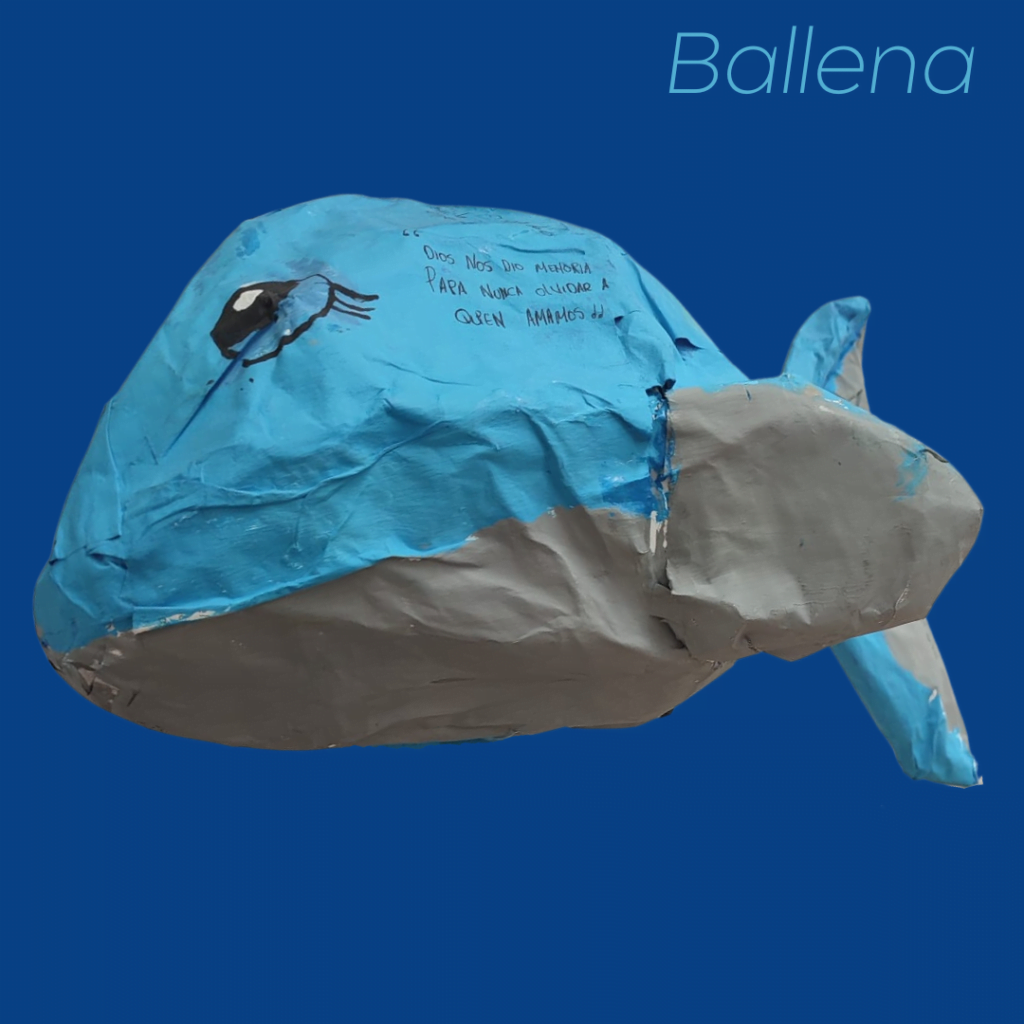

Lipa’s whale (Ballena)

Lipa remembers one special afternoon on the beach in Chocó with her godmother, who she hasn’t seen for a while, and she hopes one day to be able to share more ‘moments of love and peace’ like this one.

‘It’s a blurry memory and I don’t know how old I was, I just know that I was little. I remember we were walking on the beach and talking. The colour of the water was crystal clear and the sun kissed the sea.’

‘From one moment to another I managed to see the silhouette of a whale; I saw his tail and huge body dancing in the sea, it was hypnotic. With the sunset in the background, this beautiful animal seemed like a hallucination.’

‘Every time that moment comes to mind I remember the tranquillity and joy that I felt.’

Our partner Tiempo de Juego developed the project activities in three different centres in Bogotá. The first is the “Arcadia”, a Protection Unit from the District for the Protection of Children and Youth (IDIPRON). The second is “Semillas de amor” foundation, which is a therapeutic centre specialised in caring for girls and young women who have been victims of rights violations and/or who have problems with drug addiction. The third is “Junior Masculino” which is an institution specialised in caring for boys and young men who have also been victims of rights violations and/or have substance abuse problems.

The aim of the project is to develop audiovisual projects that could help the participants to express their opinions of themselves. The purpose is to promote self-care and mental health through artistic exercises. Some topics that have been addressed include s “Expressing Emotions”, “Self-Esteem”, “Learning to Be Calm”, “Thinking Positively About Ourselves” and “Creative Thinking”. They talked about these topics and themselves through strengthening their technical skills related to music and video production. They made a song and a video clip about their life and dreams.

The project also focuses on building skills in critical thinking, empathy and managing emotions, as well as planning and leadership abilities to help the children and young people prepare for society when they leave these centres. Sport and other playful activities are a key way in which TDJ teaches these skills, for example through football they learn assertive communication and teamwork.

Why we do not use the term ‘child soldier’

- The term ‘child soldier’ invokes some misconceptions about what the role entails:

- ‘child soldier’ assumes that all children associated with armed groups are armed and fighting – many actually take on household chores, are used for sexual exploitation or for sending messages or spying

- it limits most people’s image of a child solider to boys – when in fact up to 40% of children associated with armed groups are girls

- most people think of child soldiers as only being an African phenomenon – it is thought that CAAGs are currently active in Afghanistan, Burma, Central African Republic, Chad, Colombia, DR Congo, India, Iraq, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Thailand and Yemen (Paris Principles on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict 2007).

‘A child associated with an armed force or armed group refers to any person below 18 years of age who is, or who has been, recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, spies or for sexual purposes’ (Paris Principles on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict 2007).

More News

Bringing Colombia to London: A colourful celebration of identity, community, and joy

Designed to celebrate and strengthen cultural identity, ‘Colombia Colores' offers a joyful and immersive experience where children explore Colombian heritage through singing, storytelling, traditional music, dance, and play.

Read MoreMy Body, My Rules: The Right to Say NO

You have the right to decide about your body. You have the right to say NO And no one, absolutely no one, has the right to force, manipulate, or pressure3 May 2023

Read MoreMi cuerpo, mis reglas: El derecho a decir NO

Tú tienes derecho a decidir sobre tu cuerpo. Tienes derecho a decir NO. Y nadie, absolutamente nadie, tiene derecho a obligarte, manipularte o presionarte a hacer algo que no quieres.

Read MoreCommunity as a Superpower: Supporting Venezuelan Refugees in Colombia

In times of crisis, the importance of community becomes especially clear, particularly for children. Displacement, instability, and hardship can leave young people vulnerable, uprooted from familiar environments, and cut off3 May 2023

Read MoreLa comunidad como superpoder: apoyo a los refugiados venezolanos en Colombia

En tiempos de crisis, la importancia de la comunidad se hace especialmente evidente, sobre todo para los niños y niñas. El desplazamiento, la inestabilidad y las dificultades pueden dejar a3 May 2023

Read More