Have you ever seen a child selling sweets on the street, working in a shop, or carrying heavy things while others are at school? Maybe you noticed it and thought it was normal, or perhaps you thought they were just helping their family. But the truth is that many children and adolescents are being forced to work, and they don’t always do it by choice or under fair conditions.

This blog isn’t here to give you a “boring lecture.” We want to clearly explain what child labour means, why it’s a problem, and how you, as a child or adolescent, can recognize it, protect yourself, and help others.

What is child labour?

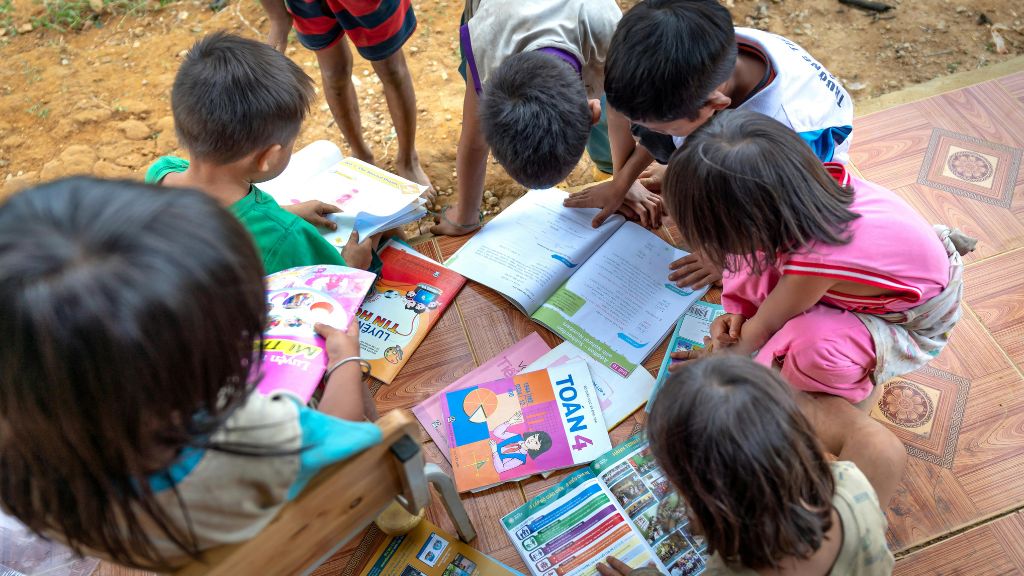

Child labour occurs when a child or adolescent engages in activities that affect their health, physical or mental development, or prevent them from attending school and enjoying their childhood. It’s not just about having a job: some forms of work are acceptable, such as helping out at home with simple tasks or voluntarily taking part in activities for educational purposes. But when work replaces school, puts their safety at risk, or is done out of obligation, we are talking about exploitation.

In Colombia, according to figures from DANE, over 460,000 children aged 5 to 17 were working in 2023. Many of them work on the streets, in the countryside, in mines, in street vending, or even in households looking after others without access to education or rest. And although it may seem like they are helping their families, in reality they are being deprived of their right to learn, play, and grow up healthily.

Why is it a problem?

Working as a minor is not “growing up fast” or “being useful.” On the contrary, it can cause serious harm:

- Physical problems: carrying heavy loads, using dangerous tools, or being exposed to the sun, dust, or toxic substances can make you sick or leave lasting damage.

- Mental and emotional impacts: working under pressure, without rest, or being mistreated can cause anxiety, sadness, and mistrust.

- Loss of education: many working children leave school or struggle to concentrate, limiting their future opportunities.

- Normalisation of violence: some come to accept shouting, hitting, or abuse as part of work, when in fact these are forms of mistreatment.

And the most serious consequence: starting work at such a young age teaches children that their rights don’t matter, that they must obey without question, and that their dreams are unimportant.

Is it the same to help around the house?

No. Helping out at home is not the same as child labour. Sweeping, making your bed, washing the dishes, or looking after a pet – as long as it’s for a short time and doesn’t put your health or education at risk – is part of learning and family life.

But if you are made to work for hours, can’t do your schoolwork because you are caring for adults, aren’t allowed to rest, or do dangerous tasks without protection, that is no longer helping: that is exploitation.

And if I know a child that is working?

It’s important to understand that no child or adolescent should feel guilty for working. Often, they do so because their families don’t have enough income, or because they’ve been taught from a young age that working is an “obligation.” That’s why, rather than judging, we should help change this reality.

What can you do if you know someone in this situation?

- Listen without judging: sometimes they just need to be heard. Don’t blame them or tell them they’re doing something wrong.

- Tell a trusted adult: this could be a teacher, a school counsellor, a responsible family member, or someone who knows who to contact for help.

- Stay safe: don’t confront employers or take action on your own. There are organisations that can act safely.

- Call the helplines: in Colombia, you can contact the ICBF (line 141), the Police for Children and Adolescents, or the Family Commissioner’s Office if you believe there’s a serious situation.

What if I'm the one working?

If you’re reading this and you yourself are working in conditions that harm you or stop you from studying, there’s something very important you need to know: you have the right to say “enough.” You are not alone. There are people, organisations, and institutions that can help you.

Asking for help isn’t easy. Sometimes there’s fear, shame, or doubt. But when you defend your right to study, to play, to be healthy, and to have a dignified life, you are being brave. You are protecting your future.

You can reach out to your school, a Family Commissioner’s Office, a local ICBF Centre, or even write a letter asking for protection. The important thing is not to stay silent.

What does the law say?

The Colombian Constitution, in Article 44, states that the rights of children take priority over the rights of others. One of these rights is to be free from labour exploitation.

The Childhood and Adolescence Code (Law 1098 of 2006) also prohibits child labour. Article 35 specifies that anyone under 15 cannot be employed in any type of work, and those aged 15 to 17 may only work with permission from the ICBF and under safe conditions.

The law protects your right to study, to live free from violence, and to grow up in a healthy environment. If someone makes you work without rest, without fair pay, or without regard for your wellbeing, they are breaking the law.

What can I do now?

Speak up: the more people know what child labour is, the easier it will be to detect and prevent it.

Stay informed: reading, asking questions, and sharing blogs like this makes you stronger against any form of abuse.

Report with support: if you or someone you know is being exploited, don’t hesitate to seek help.

Believe in your rights: never think you are “less” for being a child. Your voice matters, your life matters.

Child labour is not a form of teaching, nor a test of character. It is a form of injustice that robs children of the most valuable thing they have: their childhood. As a society, as schools, as families, and as children themselves, we must learn to recognise it and act.

Remember: if a child works like an adult, they lose something they can never get back—the time to simply be a child. We all have a responsibility to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Written by: Juan Pablo Manjarres Varón – Teacher, Law student, and Certified Teaching Professional. Columnist and volunteer at Children Change Colombia, committed to the rights of children and adolescents and to strengthening education.

This blog post is a guest contribution. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of Children Change Colombia.