Latin Americans have long formed part of London’s rich multicultural tapestry, but a lack of recognition and representation has left many feeling like members of an “invisible” community. In 2024, this was a key motivation for Children Change Colombia’s highly successful first UK-based project, Colombia Colores, which has recently restarted for its second year. Colombia Colores fits into a much broader continuum of places and projects that London’s Latinos have cultivated to remain connected to their roots and the wider diaspora.

Latino London: past and present

London’s Latino connection dates back to the revolutionary era across the turn of the 19th century, when liberators and exiles such as Francisco de Miranda called the city their home, dining with British radicals like Jeremy Bentham and campaigning for independence. At 4 Duke Street in Marylebone, a Blue Plaque commemorates Simón Bolívar’s three-month stay in the British capital in 1810, during which El Libertador attempted to rally support for the Caracas Junta in its struggle against the Spanish Empire.

This year (2025), Colombia and the UK are celebrating 200 years of diplomatic relations.

Today’s Latin American diaspora has its roots in more recent political upheaval on the continent, as Chilean, Uruguayan and Argentine exiles crossed the Atlantic to flee military dictatorships in the 1970s. Colombians who arrived in that decade as migrant workers pushed by poor coffee harvests were soon joined by thousands of asylum-seekers fleeing the internal conflict. Later, further arrivals came from countries such as Brazil, Peru and Bolivia, in search of work and political stability. And after 2008, a new generation of Latin Americans came to the UK as onward migrants – many with EU citizenship – now escaping the impact of the global financial crisis in southern Europe.

While exact figures are elusive for reasons explored below, researchers such as Cathy McIlwaine, a geographer at King’s College London and former Children Change Colombia trustee, suggest that the UK’s Latin American diaspora numbers in the hundreds of thousands. A majority reside in London, where they represent one of the fastest growing ethnic communities. Latin Americans tend to be concentrated in the capital’s inner city boroughs such as Lambeth and Southwark; within the latter, the Elephant and Castle area is even known informally as London’s “Latin Quarter” due to the density of Latino residents and businesses.

The issue of visibility

Despite this longstanding – and growing – presence in the UK capital, “invisibility” is a word often associated with Britain’s Latino community, whether in academic studies, or in grassroots campaigns such as the July 2023 Trafalgar Square demonstrations organised by community group Let’s Talk Latinx under the slogan #StandUpToInvisibility. But to what does this refer?

For one thing, the community still lacks official recognition as an ethnic group. Since 2012, the community-led Coalition of Latin Americans in the UK (CLAUK) has tried to rectify this, succeeding in several London authorities. But at the time of writing, Latin Americans still face having to tick “Other” on the 2031 national census. As research by academics and frontline charities has highlighted, this lack of official data can mean that problems disproportionately impacting Latino Londoners go unacknowledged in conversations about public policy strategy.

But this “invisibility” goes beyond the lack of a dedicated census category. As filmmaker Romano Pizzichini showed in his 2019 short film, More Than Other, many Latinos perceive a lack of cultural representation and awareness, even within London’s broader diversity. Although its vibrant multiculturalism was something that she valued while growing up in the capital, 30 year old Bia Ratton, who was born in Brazil, notes that “Latin American representation was always missing in any cultural events I attended, and there was little to no reference in general to the Latin American community living in the UK”. Instead, Bia’s connection to her roots was kept alive mostly through being able to visit family in Brazil, which she describes as a privilege.

Charity Action For Children has emphasised that a lack of explicit and positive representation can particularly impact children and young people who are still forging their own sense of identity and are vulnerable to any implication that their own background is worth less than that of their peers. And unfortunately, damaging stereotypes can fill the void left by a lack of representation – a reality highlighted and challenged by the pointedly-titled play “My Uncle is Not Pablo Escobar”, which doubled as both a fictional story centring on Latin American women’s experiences in London, and a platform for real campaigns for Latinx community representation.

Regaining representation: Latino projects and places

In their 2020 book about Latin American migrants in London, researchers Patria Roman-Velazquez and Jessica Retis highlight the role of cultural practices in providing “empowerment, resistance and healing”. London’s Latinos have cultivated important spaces where cherished aspects of Latino identity are preserved, made visible and celebrated. An entire Latino civil society stretches from campaign groups like CLAUK, to the old Latin American market in Elephant & Castle, recently (partially) reborn in Walworth, to south London’s “Liga Latinoamericana de Clapham”, a grassroots league in a city whose professional teams have treasured the passion and flair of Latin American football ever since the Argentines Ricky Villa and Ossie Ardiles signed for Tottenham Hotspur in 1979.

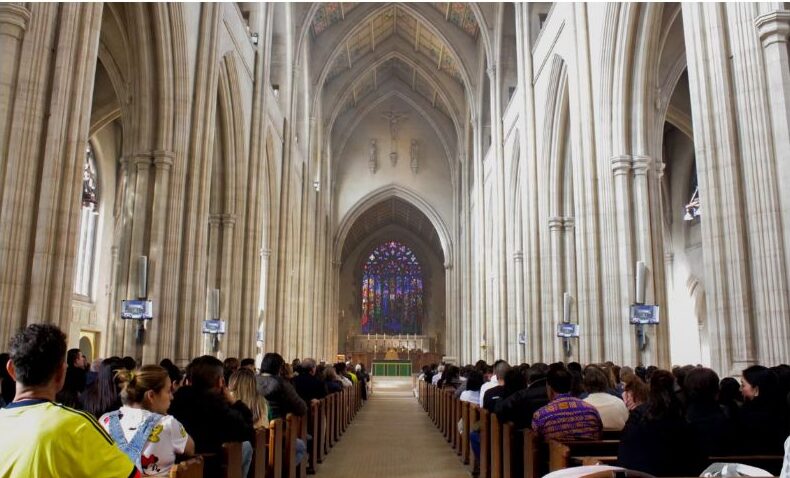

One example of these spaces is the Latin American Chaplaincy based at St Anne’s Roman Catholic Church in Vauxhall. Andreo Sotelo, a volunteer at the chaplaincy who moved from Peru to London, says that the blend of different Latin American nationalities there allows members to learn from and “enrich each other” culturally, experiencing “the food, traditions, and particular religious practices of each country”. Andrea also observes that with a frequent gap in English proficiency between UK-born children and many first-generation migrant parents who work long hours and have limited opportunities to focus on language skills, seeing the children “receive the catechism in Spanish allows them to continue that link” to their countries of origin.

Performing arts can also be an important vehicle for feeling connected to a diaspora identity. Members of the Brixton-based Talentos School of Dance seek to use “art expressions and leisure activities” to “strengthen our Latin American roots and encourage integration between communities”; by bringing vibrant folk outfits and dances to central London landmarks, they have offered a particularly striking example of recovering visibility.

Children Change Colombia’s first UK-based project, Colombia Colores, aimed to create a space where the children of London’s Colombian diaspora could consolidate and celebrate their roots, with an eye on the considerable research highlighting the importance of cultural identity and community connection for children’s self-esteem. The project involved a series of free-to-attend weekend workshops that introduced children to diverse aspects of Colombian culture, from learning about the beliefs and languages of the Indigenous Wayuu, Muisca and Arhuaco peoples, to one session making guasas, an instrument used in Afro-Colombian Currulao music, to exploring Colombia’s vibrant biodiversity.

In total, 136 children experienced the first set of Colombia Colores workshops, and the project’s Pedagogical Coordinator, singer-songwriter María Mónica Gutiérrez (a.k.a. Montañera), was pleased to report that the children showed growing curiosity about Colombia as well as building friendships and becoming more comfortable speaking Spanish throughout the sessions. As Colombia Colores continues in 2025, the aim is that even more children will feel closer to their roots and prouder and more visible as both Colombians and Latinos.

Conclusion

No community should feel “invisible” in a city that prides itself on its diversity and multiculturalism. Yet despite a long history in London and a sizeable and growing population, that is how many Latinos have described themselves. Allies can and should support the visibility of Latin Americans in London, and there are many ways to do so, from visiting the reclaimed Latin market space near Elephant and Castle, to backing CLAUK’s future efforts to secure official recognition. By supporting cultural initiatives like Colombia Colores, we can play a crucial role in ensuring that young Latinos feel connected to their identity. Educators could also follow a similar model: by introducing children to communal role models and taking time to celebrate aspects of Latin American cultures, they can attach “positive meanings” to Latino identity, resisting negative stereotypes and instilling a sense of pride. Being aware of this issue is only the first step: it is time to recognise and uplift Latinos as an important part of our vibrant global city.

Written by: Joshua Newmark (Research Analyst | Writer | PhD Graduate in Modern History)

Disclaimer: This article is a guest contribution. The views, opinions, and ideas expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Children Change Colombia.